Apache Sedona: Putting the ‘Where’ In Big Data

Technologists have built distributed systems designed to process a variety of data types for many use cases. We have key-value stores, relational databases, document databases, graph databases, and even time-series database. But there’s one data and database type that has mostly eluded the hands of skilled developers: geospatial data. The folks at Wherobots who are behind the Apache Sedona project are looking to remedy that situation.

As an associate professor of computer science at Arizona State University in the 2010s, Mohamed “Mo” Sarwat taught his students about the different types of databases and distributed systems. He covered the various attributes of the systems, such as Apache Spark and Apache Flink, including their strengths, weaknesses, and the tradeoffs that inherent in this line of work. But there was something missing when it came to geospatial data.

“I looked at all the systems that I taught, and all the systems that I built and researched in my training in the field, and none of them treated geospatial as a first-class citizen,” Sarwat tells BigDATAwire. “They’re general-purpose systems, which is great…But they didn’t provide support for geospatial data, for any aspects of the physical world, despite the fact that most of the data exists out there is collected from the physical world.”

That’s not to say there were no applications designed for geo-spatial data. There are a number of popular geographic information systems (GIS) applications on the market. However, while these GIS apps are widely adopted, they typically do not provide the sort of distributed data management and processing capabilities that today’s big geospatial data demands, Sarwat says.

“I was looking at these two worlds,” Sarwat continues. “You had the geospatial world on one hand and the data and the infrastructure work on the other hand, and they were speaking different languages and were going too many different directions.”![]()

Faced with an absence in the market, Sarwat and his ASU colleague, Jia Yu, who was in the PhD program, did what untold number of technologists have done before them: They decided to build it themselves.

A New Geospatial Framework

In 2017 at ASU, after extensive trial and error, the pair released a framework called GeoSpark that extended the Apache Spark framework with support for geospatial data and processing.

The software is designed to efficiently ingest, transform, and process large amounts of geospatial data, such as that generated by satellites, GPS, phones, cameras, and other sensors.

“It’s Apache Spark, but for physical world data,” Sarwat says. “As we were getting into this kind of domain, we tried a lot of things, and it didn’t work out. That’s why the market did bite on it [Sedona], because it did not exist at all. We finally found something that can help us do that, and that’s why there’s a lot of traction for the software.”

Apache Sedona functions as a scalable data warehouse for geospatial data. Popular GIS tools functions like business intelligence tools that lets users interact with geospatial data in a very detailed way, but which lack the underlying distributed engine that enables users to work with very large geospatial data sets.

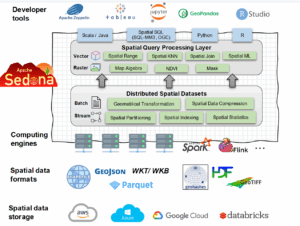

Developers can utilize Apache Sedona via standard application programmer interfaces (APIs) for Python, which is the most popular way to access Sedona, or optionally via Spatial SQL, which is an extension of the SQL standard. The open source project also features a software development kit (SDK) that Java and Scala developers can incorporate into their work.

There are intricacies to handling geospatial data that other types of distributed engines don’t face. For instance, it’s very difficult to sort and index geospatial data, Sarwat says.

“A lot of this data is actually polygonal geometries that are very, very intricate,” he says “Think of boundaries–not even static boundaries, like state or counties. I’m talking about boundaries of buildings. I’m talking about even moving boundaries, off cars or off moving objects. It’s not just an X column and a Y column, for example, in a table. It’s much more complicated than that.”

Processing these boundaries involves filtering objects and determining how they intersect with each other. These geometric computations are very compute intense, and it just doesn’t work with traditional computing paradigms, Sarwat says.

“It might work, but it will be very slow, very inefficient, and may not even scale to the size of the data and the size of compute to run on that data,” he says.

Enter Wherobots

The downloads of GeoSpark started at just a few hundreds in the beginning, but it quickly cranked up into the thousands and soon the millions. In 2020, Sarwat and Yu submitted Sedona to the Apache Software Foundation, and as of July 2025, Apache Sedona had been downloaded 50 million times. The uptake surprised them.

“To be completely honest, when we released it as academics at the university, me and my students, thought maybe like a few other people across the world and other universities would start using it,” Sarwat says. “We realized there is a gap, but we didn’t realize how big of a gap that was. The market was very thirsty for a technology like that.”

In response to the rampant enthusiasm for their project, Sarwat and Yu did what an untold number of technologists have also done through history: They decided to create a company around it. In 2022, they co-founded Wherobots to deliver a hosted version of Apache Sedona, a la the relationship Databricks initially had with Apache Spark.

Instead of trying to run geospatial workloads as user defined functions (UDFs) in a data warehousing environment, such as Oracle, Databricks, or Snowflake, they can run the workload as a standard function in a Apache Sedona cluster and get big performance gains. If they move their Sedona workload to Wherobots serverless cloud, which features more than 300 pre-built raster and vector functions such as map matching, geostatistics, and map tiles, they can see another 30% to 50% in cost savings, says Ben Pruden, head of go to market at Wherobots.

Big Geospatial Use Cases

The great thing about improving the processing of geospatial data is the number of applications that can be built. From insurance and real estate to logistics and social media, there are all sorts of ways geospatial data can be incorporated into an application. As the number of data points goes up, so too does the load on the underlying data infrastructure, which is where Apache Sedona and its Apache Spark-based data processing capabilities come in.

For example, the last-mile delivery problem is a huge challenge for companies like Amazon that strive to deliver packages to billions of people around the world. The volume of deliveries times the size of the delivery squad times the size of the developed world equals a major computational problem for Amazon. But thanks to Apache Sedona, Amazon is able to handle the challenge.

Amazon presented on their use of Apache Sedona during the AWS re:Invent conference last year, Pruden says.

“They’re taking in this data from satellite imagery, from aerial imagery, like from drones, from GPS traces coming off of their trucks that are taking packages to your house, streetside imagery,” Pruden says, “and they bring it into a system that is largely powered by Sedona to do a very large graph and then conflation of their data sets to maintain these really updated maps of the world.”

Apache Sedona is critical for providing detailed map representations that Amazon drivers use to get directly the right place within customers’ houses or apartment complex, Pruden says. “Or if you’re out in a rural area, maybe there’s a really long driveway that is not obvious that you have to figure out where to drive down,” he says. “They’re preparing all that data across the entire planet and then serving that back so that their drivers can utilize it.”

Another early adopter of Apache Sedona is Overture Maps Foundation, which is building an open reference map of the entire world. The organization started out running Apache Sedona on Spark, and is currently migrating to the Wherobots platform, Pruden says.

“Organizations like Overture and a number of others are using both our open source and also increasingly Wherobots to analyze and deliver insight and create data products for data about the physical world,” he says.

Whereobots, which is based in San Francisco, California, is still ramping up cloud operations on AWS, which the company says is a close partner. The company raised $21.4 million in venture funding in November. In the meantime, the company is looking forward to the next frontier for geospatial data: integration with AI.

“So far, AI has been really good with language, responding to us. We interact with it, and it’s fantastic,” Sarwat says. “But up until today, AI doesn’t have a very good knowledge of the physical world, like how to reason about the physical world in general…And this is what we’re focusing on, on how can we provide a data engine that can make that kind of data AI ready and make it very understandable by AI.”

Related Items:

5 Ways Big Geospatial Data Is Driving Analytics In the Real World

How Geospatial Data Drives Insight for Bloomberg Users

The post Apache Sedona: Putting the ‘Where’ In Big Data appeared first on BigDATAwire.